The win-wins of climate and biodiversity solutions

This story was originally published by The Revelator.

What’s better for plants and wildlife is better for the climate. But where do we start to accomplish the best results?

The climate is changing, and species are going extinct faster than any time since civilization began. The two crises are not independent. That’s good news—it means there are solutions that benefit both biodiversity and climate.

Nature is already our best defense against runaway increases of greenhouse gas emissions. Earth’s lands and waters currently absorb about 40 percent of the carbon dioxide human activity and natural processes release into the atmosphere. That can’t continue, though, without our oceans acidifying and plants reaching the limit of what they can absorb.

As an ecologist, I’ve spent nearly three decades working to conserve biodiversity within landscapes largely managed for food and goods production. Now, as special projects director at Project Drawdown, I study how climate solutions can benefit the planet’s biodiversity. Through all of this work, I’ve found that many climate-friendly initiatives also help with conservation. Although some solutions can come with costs or tradeoffs to plants and animals, what’s better for biodiversity is generally better for climate. That means protecting and restoring nature needs to be a critical part of an all-of-the-above set of solutions for reducing the total amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

Stopping or slowing habitat loss, for example, is good for biodiversity and the climate. Plants absorb carbon dioxide from the air to grow, and a portion of that carbon is stored in plants and soil. Habitat loss releases the carbon stored in soil and plants, so it’s a major source of emissions. Tropical deforestation alone, mostly to clear land for agriculture, accounts for 10% of global greenhouse gas emissions. If deforestation were a country, it would be the third biggest greenhouse gas emitter, trailing only China and the United States.

Climate solutions can also enhance nature’s role as a carbon sink — its ability to store carbon. A complex habitat structure supports more species and stores more carbon at a greater rate. Protecting, restoring and enhancing biodiversity on managed lands all enhance sinks.

In other words, protecting natural habitat both reduces production of greenhouse gases and boosts nature’s ability to sock them away.

But with so many ecosystems under threat, and the climate crisis getting worse by the day, where do we start?

Protect What’s Left

To achieve the most benefits for both biodiversity and the climate, we must start by protecting the Earth’s remaining intact ecosystems.

Protecting all remaining habitat is, of course, important, but destroying intact areas disproportionately affects species loss compared to further destroying fragmented areas. And clearing and degrading intact areas is also a double whammy for climate. The existing carbon stock is emitted and the habitat’s ability to act as a sink is lost.

It’s like the gift that keeps on giving—except it keeps on taking away.

And the impact compounds over time—when you include the foregone sequestration, the carbon impact over a decade of clearing tropical forest can be six times higher than the immediate emissions alone.

Intact areas have more carbon in the vegetation and soils and a higher species diversity than degraded areas. Intact areas are also better carbon sinks. They store carbon at a faster rate than degraded areas. For example, nearly a fifth of the world’s forests are legally protected, yet they store more than a quarter of the carbon accumulated across all forests every year.

But protection is not on pace with loss. Forest protected areas almost doubled from 1992 to 2015, from 16.6 to 32.7 thousand square miles. During that same time, nearly 200,000 square miles were deforested. If you had a gap like this between savings and withdrawals in your bank account, you would — and should — be very, very worried. We need to accelerate the rate of designating new protected areas.

Protected areas need not be parks. In fact, many of them shouldn’t be parks. Indigenous communities play an essential role in protecting biodiversity and reducing the threat of climate change around the world. Areas managed by Indigenous people are commonly more intact than neighboring private and public lands. Securing land and water rights for Indigenous communities is not just good for nature. It helps protect identity and sovereignty.

Restore What We Can

So what about habitats that have been altered by human activity? They’re still important. Restoring disturbed lands and waters to a natural state boosts their ability to conserve biodiversity and increases their potential to suck carbon from the atmosphere and store it in vegetation and soils.

Restorations generally have lower species diversity and a simpler structure than intact ecosystems and are not as effective at storing carbon. However, they’re an essential part of recovering ecosystems where only small fragments remain, such as the grasslands of North America, Brazil’s Atlantic Forest, Mediterranean forests and scrublands in North America, Europe, and Africa, and dry forests of Asia.

Unfortunately, the list of endangered ecosystems is much longer than those few examples.

Restorations also are less beneficial than protecting intact land from a climate perspective, since carbon accumulates slowly over decades or hundreds of years. And we can’t assume that today’s acorns will become tomorrow’s oak trees—or, if they do, that those trees will escape harvest, natural disasters or pest outbreaks long enough to serve as meaningful carbon sinks or legitimate sources of carbon offset credits.

Enhance Biodiversity on Working Lands

Of course, not all lands can remain natural. We need space for farms, wood production, roads, homes and businesses. Croplands and rangelands cover 38% of all land on Earth. Forests cover about another third of the land, of which 60 percent is managed for timber and other forest products. That means about 58% of all ice-free land is used to produce food and forest products.

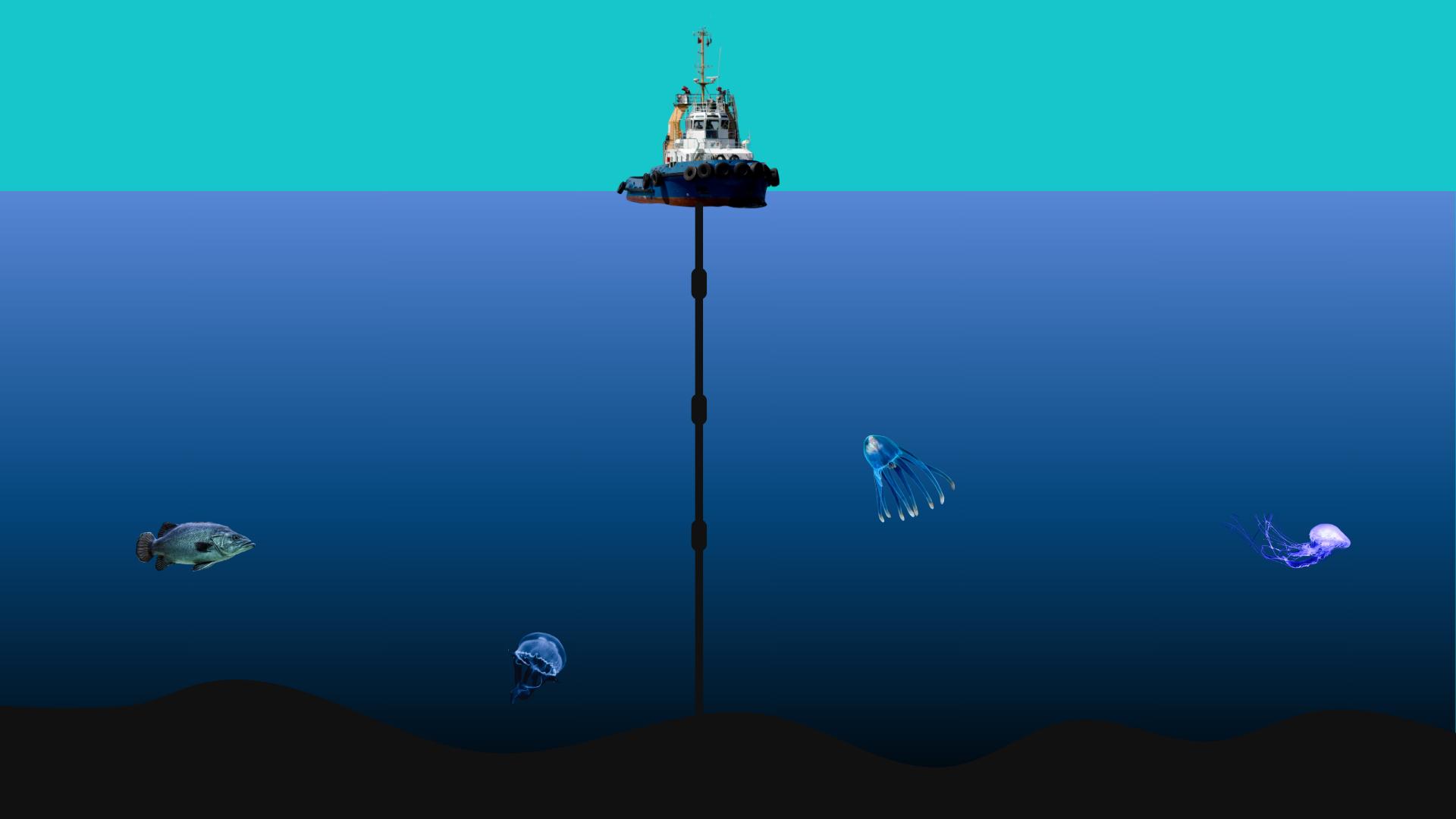

Several climate solutions that can be implemented on agricultural lands, such as agroforestry and managed pastures, also benefit biodiversity. Although these solutions may provide smaller benefits at the scale of a farm field or forest stand, a little bit of change everywhere can add up to a lot of carbon stored and locally provide species diversity, habitat structure, and ecosystem function. Ocean-based solutions exist too, and researchers are learning more about how they benefit both biodiversity and climate.

Targeting Actions

Each ton of carbon is equally important. The potential avoided emissions and carbon stored for several solutions are summarized in two key publications, The Drawdown Review and Natural Climate Solutions.

For biodiversity, some land, water and coastlines are more important than others. How much land and water do we need to protect biodiversity? Truth is, we don’t really know. But very basic rules are true: More is better, bigger is better, more connected is better, and more geographically and climatologically diverse is better.

Initiatives like the Global Safety Net lay out a roadmap for conserving biodiversity, maintaining highly productive agricultural lands, and stabilizing climate by protecting or managing 50 percent of all ice-free land on Earth. Other efforts have identified critical areas (or frameworks) for protecting marine and freshwater biodiversity.

(Potentially Huge) Bonus Points

Several other climate solutions can indirectly benefit biodiversity. For example, shifting to plant-based diets, reducing food waste, and sustainably intensifying food production on smallholder farms all reduce the need to expand agricultural lands, the biggest cause of habitat loss and degradation.

When these solutions are implemented, agriculture’s land footprint would not only stop expanding—it could shrink. The land used for grazing or growing animal feed could instead be used to restore ecosystems or to produce fiber and fuel.

Big or Small, It Takes All

We need all efforts, big and small, to solve the biodiversity and climate crises.

Yes, we need a concerted effort among governments, companies and investors for transformational change. But individual efforts, from managing a small fish farm in a mangrove forest to protecting tiny prairie remnants, matter too. Small changes accumulate and help shift the social norm of what we expect from our neighbors, CEOs and presidents.

An all-in, all-of-the-above approach is essential. All we need are the incentive and motivation to start.